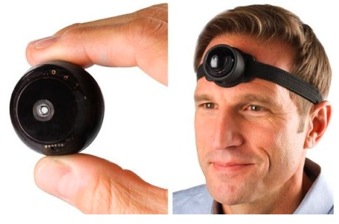

Photography in the Age of the CyborgJacob Freitas How will the world of photography look when a large portion of the population has a camera attached to their bodies at all times, capturing images at all times? Thinking of this world brings about a host of interesting questions about surveillance, journalism, and privacy. Questions about social issues like these are the first to come up, but what about Art? What will happen to photographer as an art form when every person is capturing images during every waking moment of every day? How photos are taken, viewed and valued may completely change. The first question someone might have is how far into the future is this technology, (not far by the way.) Canadian filmmaker Rob Spence who lost an eye that was damaged in a shot gun accident, and engineer Kosta Grammatis, are working on a project they call, eyeborg. They are building a prosthetic eye with a built in video camera. The prosthetic eye will be equipped with camera that is the size of a 1.5mm square, a wireless transmitter and a battery power source1. The device doesn't connect with Rob Spencer's brain, nor does it restore his sight, but it could in time. Brain Computer Interface or BCI technology establishes a direct connection between the brain to an external device2. British Telecom, one of the worlds leading telecommunication service companies, is working on a microchip called the Soul Catcher3. The Soul Catcher microchip will be implanted in the skull behind the eye and, “record a person's every thought, experience and sensation.” British Telecom expects this technology to be ready by 20254.

What does this sort of technological advancement mean for photography? Photography has always been tightly connected with technological advancement. Oil painting today is done is pretty much the same way as it was done five-hundred years ago, but you don't see many contemporary photographers carrying around large format cameras and capturing negatives on glass plates, (though there are a few, like photographer Sally Mann.) Still change has met with resistance at certain points in the history of Photography. In 1936 Walter Benjamin wrote The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In this essay Benjamin argued that the “aura” of an original work of art, which denotes artistic worth, would diminish in the age of mechanical reproduction5. Clearly the values of authentic and original pieces of art have not diminished. In 2006 an original Jackson Pollock sold for $151.8 million dollars6. While Benjamin's predictions about the aura of originality may have been wrong, we can see in hindsight how the technology that allowed for exact reproductions of images changed the art world. Jackson Pollock and other abstract expressionists, Andy Warhol's Pop Art and other art movements of the 20th century, are direct responses to the ability to reproduce images using technology.

There will always be people resistant to change and purists arguing, “Éthat isn't real photography.” As a photographer I sometimes find myself falling into that frame of mind, (no pun intended.) What I love about photography is the process, loading the film, cranking the lever and feeling the film advance through the camera, painstakingly framing a shot, hitting the shutter release, and hearing the sound of the shutter flipping up and back to take the photo. Then there is the process of developing the shots. With digital cameras all that is disappearing. Tim Wu wrote an article titled, “The Slow-Photography Movement.” In it he relates automatic and digital photography with fast food, instantly satisfying and void of almost all value. He makes a convincing argument that what is lost with fast-photography is not quality, if you can take hundreds of pictures per minute, (there is a camera that can capture 6.1 million frames in a single second7.) At least one will turn out good. What Tim Wu argues is that the experience is lost, that people are becoming detached from the process of photography8. At first this seemed like a convincing argument to me. I identified with what Wu says, and his argument is even more applicable when you consider cyborg technology. The photographer will lose all interaction with the camera as it becomes integrated with their bodies. The mechanical processes that a photographer uses to learn and understand will be replaced by programming code that they probably know nothing about. Active and careful framing of specific shots will fall away to the thousands of images captured automatically throughout the day. To me, this all seems bad thing for the artistic value of photography. It removes everything that is familiar to me about photography, but is what I identify with as photography definitive for photography? I don't feel that it is. If you compared the photography I am familiar with to photography form the end of the 19th century they could make the same arguments Wu, others, and myself would make. If I buy my film from the store, then I am detached from the process, because the Collodion process involves the photographer creating the film. It involves coating glass plates with a photographic emulsion of silver halides, and suspending the film in gelatins to form the images. It has always been that in photography the artist produced the work. With technological changes, the tech produces the work. It would be unfortunate to lose traditional film development methods. It would be losing a form of human expression, but it would be equally unfortunate, if not more so, to deny the new modes of artistic expression possible in photography through new developments in cybernetic technology. I cannot predict what the world of photography will look like when people have integrated cameras into their bodies, but I know that they will use the technology to express themselves and frame their world, just as photographers have always done. |