Menstruating Cyborgs: Insights into the Technology of Menstrual SuppressionLara Hale

Introduction

This paper discusses the cyborgization of women in the Unites States through the lens of pharmaceutically-induced menstrual suppression. A cyborg is defined as a biological organism, modified by technology (“cyber” as a prefix meaning “computer,” and “cyborg” as a cyber-organism). Menstrual suppression is an extension of the technology of oral contraceptives, herein referred to as OCs, and is defined as the pharmaceutical suppression of women's monthly menstrual cycles. Seasonale is a FDA-approved drug meant to reduce a woman's periods from 13 to 4 per year, and some physicians recommend the non-stop use of active pills in traditional OCs to halt periods altogether. This technology potently alters the physiology of its users to the extent that they are no longer natural humans, but instead function as hybrid creatures of human endocrinology and pharmaceutical technology. The long term effects of this cyborgization are unknown, but could prove to be harmful or even fatal to women. To date, no long term studies have been performed on either method of menstrual suppression. Yet this curious modern trend persists, and in fact appears to arise out of a cultural desire for the creation of non-menstruating women who maintain their sexually-appealing characteristics. Cultural attitudes towards menstruation throughout history highlight the long tradition of male fear and societal silence surrounding it. As a result of the inherent fear and shame in these perspectives, humans have used modern technology to modify women to hide, regulate, and ultimately eliminate menstruation. However, in light of the known side effects associated with synthetic hormone consumption, caution should be applied to their use over any time frame, in any form. OCs have been demonstrated to significantly increase the risk of multiple health dangers, particularly heart attacks and thrombotic events; and extension of estrogen and progesterone intake could heighten these risks. Thus, physicians and public media in favor of Seasonale and non-stop OCs promote menstrual suppression at the cost of endangering women to unknown long term adverse effects. Gender

Efforts to manipulate women's cycles are inseparable from gender relations. In a patriarchal society such as the United States, where males control the silence surrounding the female phenomenon of menstruation, the resulting ignorance serves to exacerbate gender conflicts. Furthermore, technology tends to develop under the scientific male narrative, and “little attention has been paid to the way in which technological objects may be shaped by the operation of gender interests.” Specifically, menstrual suppression may inherently serve male interests while harming females. Unfortunately, patriarchy can also result in women's neglect of their own health interests in a struggle to harness social control. Gender issues are also a feature of the cyborgization ideal – namely, the ideal of a technologically enhanced cybernetic male. As feminist technologies researcher Sharra Vostral emphasizes, “There is a long-standing tradition of defining males as the universal human. As such, men do not menstruate, and women do, thus marking women as different and menstruation as unique to a sex.” This sex-separation could potentially exclude women from the larger picture of technological enhancement; however, technology itself can be used to mask “undesirable” female traits. Women can thus continue to be valued in the context of sexual objectification, without the negativity associated with menstruation. Women actively participate in the formation of this modified sexual identity: “Roberts (2004) argued that women, as members of a culture that sexualizes or objectifies their bodies, are motivated to distance themselves or dissociate from bodily functions, such as menstruation, that are deemed incompatible with their sexual attractiveness or desireability.” The combination results in a society where both men and women express interest in eliminating menstruation.

The implications of non-menstruating women extend even beyond gender into issues of race and class. Since menstruation is often perceived as “dirty,” its elimination represents a higher level of cleanliness, a characteristic that has historically been used to assert the superiority of one group over another. Non-menstruating women can therefore be categorized into culturally favored groups. In this way, it is likely that the negative health consequences of menstrual suppression will be dismissed since “within the model of perfectible civilization, cleanliness represent[s] human progress, and indicate[s] a level of personal control and bodily efficiency.” Due to a long history of societies that highly value the sexuality and cleanliness of non-menstruating females (and reject menstruating ones), American women are engendered with the sense that the utilization of menstrual suppression technologies is more important than their long term health. History

Repugnant attitudes towards menstruation in modern societies are in part an aggressive reaction to former cultures that embraced women and their cycles (often worshiping women and placing them in powerful positions). Patriarchies developed as the dominant societal structure in violent contrast to the matriarchal tradition, in which the natural cycles of environment, animals, and humans are highly valued. Matriarchies can be described as having “an essentially organic, vegetal, non-heroic view of the nature and necessities of life,” whereas for the patriarchies that prevailed after the Iron Age “the battle spear and its plunder were the source of both wealth and joy.” The transition from matriarchy to patriarchy resulted in the shunning of many “feminine” traits, including menstruation.

Throughout Western patriarchal history, menstruation was both poorly understood and fiercely rejected. As early as the times of ancient Greece, influential men like Aristotle argued that menstruation is a symptom of women's inferiority. A woman's monthly period was referred to as either Gynaikeia (the womanlies) or Katamenia (the monthlies). Physicians would misguidedly attempt to assess the health of woman based on the color, consistency, and even odor of her menstrual flow. However, the frequency of menstrual periods was largely less than with modern women: “That women in ancient times could miss their normal menstrual cycle was explicable; their diet was often poor and they were often pregnant.” Therefore, the ability of physicians to assess the function of menstruation was much impeded (with theories ranging from it being the same form of blood as in the veins to being the material from which fetuses are formed), resulting in distorted perceptions of the menstrual period as being a time of sickness and insanity – both of which reinforce fear. Fear

The cultural integration of ridiculous views of menstrual sickness and insanity are made possible because of male fear that pervades such a gender-specific event. Since men have the capacity to empathize with cycling, bleeding and pain, but cannot fully relate to menstruation, they tend to view it with a combination mysticism and horror. Medieval physicians' evaluations of the properties of menstrual blood betray their reactions connected to it: “[It] might have powers both healing and harmful, sometimes natural, sometimes magical.” These perceptions resulted in the perpetuation of frightening accounts of the menstrual period's effects. The Secrets of Women (c. 1300) claimed that menstruating women who peer into mirrors permanently stain the glass with a “bloody cloud.” Even more disturbing is the description of the contagiousness of menstrual blood: Here it is explained, in accordance with Aristotelian science, how the 'unclean matter' that is menstrual blood seeps out through the sweat holes in women's eyes, affecting the air around them, and then enters the children through the pores in their own eyes. Even the cradle is thus not protected against violation by menstrual blood. Grown men can be equally polluted: speaking to a menstruating woman, for instance, makes the distinctive male voice hoarse, again through the transmission of 'unclean' air. Such terrifying regard for menstruation led to the identification of menstruation as a malignancy in women that should be destroyed, or at least avoided, at any cost. Although the centuries have allowed for a number of more holistic, empathic views of menstruation, fear has tinged Western medicine's foundations. Approaches shadowed by this fear allow for the consideration that, indeed, dangerously medicating women to suppress their menstrual cycles is preferable to letting the cycle continue naturally.

Sickness and Insanity

Historically, women were perceived as medically ill based on a variety of menstrual phenomena; which developed into an overall modern categorization of menstruation as an abnormality. In ancient and medieval history, the total lack of periods in young women was viewed as pathological, but the age of onset and accompanying physical changes could also be diagnosed as illnesses. Further, Western religions uniformly institutionalized negativity towards menstruation – with Christianity, Judaism, and Islam all rejecting women during menstrual periods as “unclean.” Eventually, these attitudes were solidified and cemented into educational literature. Modern Western institutional medicine regards menstruation to be an illness, requiring treatment (often in the form of pregnancy). As early as the 19th Century, biomedical textbooks associated menstruation “with the processes of hormonal 'decline,' 'degeneration' of the corpus luteum, 'deterioration' or even 'denuding' of the uterine lining, or 'loss' of blood and 'lack' of fertilisation [which] can be linked to cultural attitudes about production and the proper function of the female body.” Today, reproductive physiology literature goes so far as to portray menstruation as an “evolutionary abnormality.” This trend fits smoothly into the development of technologies meant to eliminate menstruation; as menstrual suppression is seen as a treatment for not just a temporary illness, but a full-on genetic malfunction.

Menstruation as illness is not limited to the body; the 1800's saw the rise of menstruation diagnostics in terms of mental health. Women demonstrating any manner of unbecoming behavior could be excused or sent to mental clinics on the basis of “insanity by menstruation.” The limitations of medical investigation to that point lent society to perceive basic hormonal fluctuations as erratic, unpredictable dips and spikes that sent women into outrageous frenzy. Historian Julie-Marie Strange describes a female mental patient's 1856 suicide attempt by strangling herself with a menstrual napkin as “an arresting, if dramatic, metaphor for the experience of menstruations defined and understood by medical practitioners in Victorian Britain: women would never enjoy equality with men because they were stifled and suffocated by the inherent sickness of their own biology.” In 1883, Dr. George Austin even coined the term “erotomania” to describe the insanity that women experienced when attempting to “overwork the brain” and neglect leisure during menstruation. Using menstruation as a evidence, women are not only viewed as inferior to men, but also physically ill and mentally uncontrollable. In this way, menstrual suppression technologies are seen as a way to both treat a woman's deleterious body and stabilize her seismic mind. Feminism of Menstruation

The marginalization of women because of their menstrual cycles carried forth into the movement for women's rights. In some ways, the movement appeared to be laying the ground for improving views on menstruation: “The proliferating uncertainty surrounding the relationship between menstruation, general well-being and mental health was inseparable from the movement towards campaigning for women's rights and political representation and the growing numbers of women entering the medical profession, not least because such women held a vested interest in proving the biology need not disable women's opportunities or rights to equality.” However, the newer narratives presented the former menstrual etiquette in revised forms – still approaching menstruation as something to be concealed and managed. Furthermore, conceptions of menstruation-induced insanity were imposed upon activists to explain their toward behavior. Vostral refers to the media presentations of the time: “A 1912 article in the New York Times charged that the woman's movement was filled with militant suffragists whose minds suffered from 'the reverberations of her physiological emergencies.' These physiological emergencies—menstrual periods—explained the cause of their mental disorder, because as the logic followed, only unfit women would demand the right to vote.” Facing the apparent choice between being sidelined because of menstruation or masking the event to conform with men, women selected concealment. Technologies of the 20th Century designed to improve the “sanitation” of menstrual periods became a popular way hide their cycles and “defy recommendations about rest and curtailment of activities” during their periods. Menstrual Sanitation Technologies

The pressure on women to conceal menstruation resulted in, foremost, shame, but also small efforts to use technology to assist in the veiling. Safe and comfortable menstrual sanitation technologies have not been prioritized because “in a society that values cleanliness, stained clothing can be read as a moral, and not technological, failure.” In the mid-1900's when businesses realized that money could be made on the sale of these items, redesign and advertisement of pads and tampons took off. They were so economically successful that “Johnson & Johnson hired efficiency expert Lillian Gilbreth to study the existing market in order to create the best new sanitary napkin.” The profitability of menstrual sanitation encouraged the modern belief that technology can effectively address the “problem” of menstrual periods. Women embraced menstrual sanitation technologies as a way of “passing” as non-menstruating females, while still possessing qualities of sexuality and productivity. Tampax commercials took advantage of this alteration of identity to emphasize that tampons could allow a women to participate in activities despite her menstrual periods. The culture surrounding the effectiveness of sanitation thus “imbues technologies with the power to transform.” Unfortunately this approach of using technologies to conceal menstruation also feeds into negative attitudes about it: “The shame and secrecy surrounding menstruation as well as the fear that one's menstrual status will be discovered is perpetuated by menstrual product advertisements and menstrual education.” This continued negativity so reinforced women's low esteem for their menstrual cycles that, by the latter half of the 20th Century, they were primed to accept pharmaceutical menstrual regulation in the form of OCs.

Pharmaceutical Contraceptives

The first pharmaceutical contraceptive was isolated in 1927 as an ovarian extract, and the FDA approved the first birth control pill, Enovid-10, in 1960. Although the purpose of pharmaceutical contraceptives is primarily the prevention of pregnancy, their prescriptive uses range from treatment of acne to aesthetic menstrual suppression. To mimic natural menstrual periods, they were originally designed to stimulate bleeding once a month, an event that results from the sudden lack of synthetic hormones and referred to as “withdrawal” bleeding. This means that even though OCs regulate women's hormonal conditions and suppress the natural menstrual cycle, women still experience the stigmatic menstrual blood flow each month. So even though some ten million women in the United States use birth control, these women still harbor a desire to eliminate their bleeding. Since negative attitudes about menstruation are particularly present in young adults, women in more sensitive stages of hormonal development are more likely to use pharmaceuticals to suppress menstruation. But the preference for reducing the frequency of menstrual periods is certainly not limited to youth: “Actually, the most frequently preferred bleeding pattern for women between the ages of 15 and 49 [is] less than once a month or never.” Unbeknownst to many of these women, though, is the broad health implications of artificially manipulating the body's hormones. The endocrine system is a complex system of interdependence, feedback, and synergy, and it affects a number of essential physical processes. As hormonal health expert Susan Rako describes, “All sex hormones affect physiological systems, including cardiovascular health, bone metabolism, cognitive function, sexual response, and sexual attractiveness. The fertile menstrual cycle serves more than just the next generation. A fertile pattern of hormonal secretion promotes general health and well-being.” Given the limited understanding of these systems, especially in terms of individual variation, altering them on a daily basis is somewhat like Russian roulette – the health outcome is a gamble. In spite of the dangers involved, pharmaceutical company advertisements present these technologies as the “next step,” and portray a positive progression in to the future. But how is subjecting women to greater health risks for the sake of aesthetic convenience “progress?” This form of public promotion of advancement has gone awry in the past, as well. In the 1980's, the new-and-improved Rely tampons were “linked to the deaths of thirty-eight women due to Toxic Shock syndrome, [and] revealed how the technological fix, meant to free women by hiding menstruation, failed.” Likewise, redesigned second- and third-generation OCs actually confer higher risk of ischemic stroke than first-generation (due to the added progestin). Since improvement cannot be assumed, it would be well-advised that the FDA conduct long term studies to determine safety – so that women who choose to take menstrual suppressants can at least have access to information on the risks. These studies should also take into consideration the positive effects that women will not experience that are associated with natural menstruation. Natural Periods

Recent investigations into the impact of the hormonal shifts that occur during menstrual periods expound the multiple health benefits of menstruation. These positive effects reverberate throughout a woman's mind and body: prevention of arterial wall changes (associated with heart attacks and strokes), maintenance of bone density, vaginal lubrication, regulation of monoamine oxidase (MAO) (which metabolizes neurotransmitters that affect mood), and lowering of blood pressure. Notably, many of these perks affect women over the long term – the absence of which is sometimes attributed to other factors or is not felt keenly. This aspect makes it more difficult for women to internalize and appreciate the positivity of menstruating and leave them more attracted to menstrual suppression. One current direction of menstruation research is that of determining whether menstrual periods may indeed harm women. These researchers and social scientists propose that menstruation may be responsible for a number of health issues, “including anemia, arthritis, asthma, dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, epilepsy, myomas and premenstrual syndrome.” Thus far, there is no reproducible evidence that menstruation is the cause of these problems, and two thirds of surveyed doctors disagreed that this could be the case. Given the cultural attitudes towards menstruation delineated in this paper, it is reasonable to be highly critical of scientific investigations whose hypotheses reinforce the status quo fear and shame related to periods. Oral contraceptives that inherently alter menstruation, on the other hand, have been show to have serious health impacts. Traditional Oral Contraceptives

OCs have also been associated with increased risk of breast cancer, invasive cervical cancer, and thrombotic events (deep vein clots, pulmonary embolism, heart attack, and stroke). Breast cancer is suspected to be related to the perpetual exposure to progesterone, which in natural cycles coincides with “the greatest proliferation of breast tissue cells.” In a 1983 UK study comparing some 6,838 women on OCs with a women using IUDs, cases of invasive cervical cancer appeared only in the OC group. Thrombotic events in women using second-generation OCs triple over the base rate; whereas in women using third-generation OCs, they quintuple.

The reasons that women are willing to use OCs despite these frightening risks (aside from lack of education on the subject and the much-needed communication from doctors) often fall outside the box of pregnancy prevention. In Andrist et al.'s study on attitudes about non-stop OC use (2004), researchers found that 38% of the sampled women took OCs for treatment of acne or to eliminate menstruation. It is very important to note that there are several serious and valid reasons some women choose to regulate their menstrual cycles, including severe headaches, seizure disorders, endometriosis, and risk of ovarian cancer (which OCs can reduce up to 50%). However, the representative population of such women is relatively small. These circumstances probably helped to inspire the development of a pharmaceutical designed not to further the effectiveness of contraception, but rather to suppress menstruation. “Extended Cycle” aka Menstrual Suppression

Prior to the approval of drugs specific to menstrual suppression, physicians prescribed non-approved drugs for the purpose, including both extended use of the standard OCs (which involves skipping the placebo week) and “the shot” (Depo-Provera). Since these drugs are not approved for this use, related clinical trials are essentially nonexistent. Further, physicians often fail to inform patients about the side effects that are known, potentially crippling a woman who merely wanted to do away with the inconvenience of monthly menstrual bleeding. In the case of bi- and tri-phasic OCs (different doses of hormones in different weeks), taking only active pills results in a drastic shift in hormone dosage between weeks and unwanted breakthrough bleeding and spotting. Worse is the case of poorly advised use of the shot: All too frequently, women are injected with Depo-Provera without forewarning about its potential side effects and disturbing risks, which include initial bleeding and spotting, headaches, abdominal bloating, nausea, constipation, depression, irritability, fatigue, mood changes, breast pain and engorgement, varicose veins, loss of sex drive, painful intercourse, hot flashes, dry vagina, extended infertility, detrimental alterations in blood cholesterol, and bone loss leading to the early development of osteoporosis. Once a woman has been injected with this drug, no matter how miserable she may be and no matter how severe her symptoms, she has to live with the effects for three months, until it has been “used up.” Because of the unexpected effects resulting from this poorly studied form of menstrual suppression, only about 56% of women choose to continue the suppression regimen. Although there could be a number of reasons for this (including the desire to conceive), it is likely that the adverse effects and sporadic bleeding contribute. The first pharmaceutical to be developed for the specific function of combining contraception and menstrual suppression is Seasonale, which the FDA approved in September of 2003. Each active pill contains a small dose of ethinylestradiol (synthetic estrogen) and five times as much levonorgestrel (synthetic progesterone), which a woman is intended to ingest for 84 straight days, followed by seven days of placebo pills. The longest term data study of this regiment to date is two years, the first year having been the actual clinical trial (this form of research is called an “extension trial”). Further, in the short term studies that have been conducted, “none of these included an unmedicated control group, all of them were 'open label,' and few extended beyond 1 year.” The lack of controls is especially troublesome since data is meaningless if not compared to a baseline standard. Altogether, these studies represent a disappointing collection of research, which begs for redesign and extension both of time and scope.

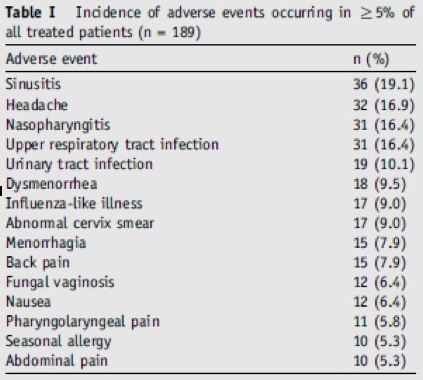

In Anderson et al.'s (2006) one year trial of Seasonique (which is Seasonale with the modification of low-dose estradiol in place of the placebo week), the results are possibly skewed by the fairly large number of the population that did not complete the study. This is suggested by the proportion of discontinuing patients who cite adverse effects (AEs) as their reason: “Approximately half of all treated patients discontinued the study prior to completing the full year of treatment...The most common reasons for premature discontinuation were AEs (16%), lost to follow-up (15%) and individual patient decision (13%).” The outcome of this study, therefore, would not include data from the approximately 8% of patients who dropped out from the adverse effects since they are not considered as having completed the study period. These drop-out rates are important to pay attention to because they can indicate not only physical issues, but also problems in regards to satisfaction and comfort in continuing the drug. There was a similar drop-out rate in the clinical trial for Seasonale, and over half of the Seasonale patients in Anderson et al.'s (2006) Seasonale extension trial were drawn from the remainder population. This would most likely create a bias towards women who had already undergone a year of the drug without adverse effects severe enough to discontinue with the study.

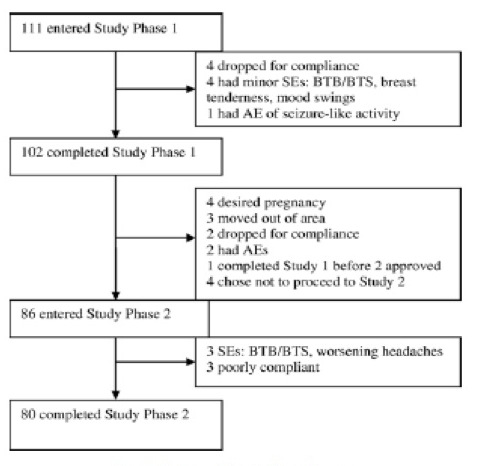

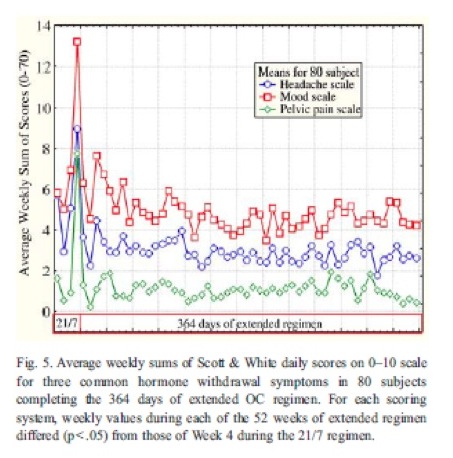

As such, the adverse effects data may in fact under-represent the adverse effects occurring in the larger population of users over several years. But since this data is not compared to that of a study control group, it is essentially meaningless. For example, “upper respiratory tract infection” rate of 16.4% does not effectively illustrated an effect of the drug if the control group (those not taking the drug) experience a similar rate. A control group is necessary to make any interpretations of the outcome of this study. In terms of drop-out rates and satisfaction, studies can be designed to better incorporate measures of these factors. Coffee et al. (2007) conducted a year-long study of an extended oral contraceptive regimen, using 3 mg of drosperinone (synthetic progestin) and 30 μg of ethinyl estradiol (synthetic estrogen) nonstop. The patients' continuation of this study is somewhat more promising than that of the FDA-approved Seasonale or Seasonique trials : The study also sought to keep track of daily symptomatology and long-term satisfaction. According to the results, extended use effectively regulated headaches and other hormonal withdrawal symptoms (similar to those of PMS), and a significant proportion of patients expressed satisfaction with the regimen :

According to the study, “At the conclusion of the 1-year extended regiment, 73 (91%) of the 80 subjects planned to continue to use OCs, and all but one planned to use the extended regimen. Compared to when subjects initiated the study, 69 (86%) considered their quality of life to be improved or much improved, 10 considered their quality of life to be unchanged and one considered her quality of life to be worse...By six months after completing the study, the 80 subjects continued to indicate a high degree of satisfaction with the extended OC regimen.” However, it is imperative to note that this study, just like with the Seasonale and Seasonique studies, both lacks a control group and is not long-term. So ultimately, this field is much in need of studies that utilize comprehensive design that examines drop-out rates, satisfaction, control groups, and long-term effects. The poor design and limited scope of these scientific studies is insufficient to establish the safety of pharmaceutical menstrual suppression. Given the nature of side effects already known about OCs, further risk from extended use is likely. According to Dr. Gerson Weiss, chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at New Jersey Medical School, “The side effects and complications of the pill will increase as more active pills are taken each year” – side effects that include heart attacks, strokes, cancer of the cervix, immune system compromise, loss of sexual appetite and reduced sexual response, and depression. Even Anderson et al. (2006) acknowledge the general blindness with which the medical world is proceeding: “The exposure to estrogen and progestin with Seasonale is higher than with a comparable 28-day cycle OC, and it is unknown if this increased exposure is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic disorders.” And further, as Hitchcock and Prior identified in 2003, there is a number of safety issues that are not being evaluated at all, including “bone and breast health, resumption of normal ovulatory cycles and fertility, and the impact of extended oral contraceptive use on the development and health of adolescents.” Sadly, the cultural drive to eliminate menstruation overrides the concern over these huge voids of knowledge. Summary

Would women really rather reduce/eliminate the symptoms of menstruation and risk premature death? Of course not. The need to even ask this question is grounded in history, Western medical approaches, cultural attitudes, and “safety” promoted by current day researchers. There is a ubiquitous push for women to renounce their menstrual cycles and use pharmaceutical technologies to regulate or suppress them. Even popular magazine articles present women as victims to a “cycle of misery,” favor quoting women who express satisfaction with menstrual suppression, and quote medical proponents twice as often as opponents. Women in the United States are submerged in a culture that fears and shuns menstruation both medically and socially; and because of the unreliable science on the safety of menstrual pharmaceuticals, the basic trust between a woman and her physician is not enough to protect her. Rather, widespread concern for the dangers of menstrual suppression would require an overall shift in the medical approach to menstruation to incorporate positive attitudes and physiological benefits. Non-menstruating, sexual female cyborgs satisfy a strong desire for the modification of natural women. As such, if this drastic physical manipulation is presented as innocuous, more and more “modernized” women will seek to engage it. Much of the approval of menstrual negativity persists out of ignorance of its historical roots – much like Harry S. Truman's conclusion that “the only thing new in the world is the history you don't know.” And although the cultural mainstreaming of this approach is disturbing, the most dangerous aspect of pharmaceutical menstrual suppression is the lack of study. Its acceptance is especially frightening for smoking and hormonally developing women, who are more susceptible to the associated risks (and also the most likely to use it). As Rako somberly observes, “Manipulating women's reproductive hormonal chemistry for the purpose of menstrual suppression [is] the largest uncontrolled experiment in the history of medical science.” The novel cyborgization of women for the sake of menstrual suppression may be harming or even killing them, a possibility that must urgently be addressed.

The most pivotal link is that of physicians, especially gynecologists. If doctors can better educate themselves on the cultural history influencing the medicine they have been formerly taught, they may be able to advise women more holistically about birth control methods. They can also help to lift the veil of silence that shrouds menstruation and encourage women to feel more comfortable discussing their cycles. Further, physicians are in a powerful enough position to put pressure on the FDA and pharmaceutical companies to conduct more in-depth, controlled, and long-term studies. It is still greatly important to women's quality of life to be able to prevent pregnancy; but this would be best carried out with full access to information and cultured love for women's natural bodies and processes. In this way, women can possess well-rounded knowledge with which they can decide where to take their own health futures and, ultimately, the future of women's attitudes in generations yet to come. Works Cited

Anderson, FD, Gibbons, W, and Portman, D. “Long-term safety of an extended-cycle oral contraceptive (Seasonale): A 2-year multicenter open-label extension trial.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Vol 195 (2006): 92-6. *Seasonale

1) http://www.dvdtimes.co.uk/images/metropolis1.jpg |