Evangelion: The Cyborg MechaDave Hansen Pilots of mecha, giant robots that make for a perfect imagining of Godzillla's worst nightmare, fuse man's body and his technology. This synergy allows viewers the dream of absolute control over the machines that make up daily life. Susan Napier's Ghost and Machines: The Technological Body outlines the science fiction anime genre mecha and its ever-present theme of the containment of the body by technology: "the mecha body clearly plays a wish-fulfilling fantasy of power, authority, and technological competence," (Napier, 2001, 86) a fantasy that extends no further than the screen. The mecha genre offers a continued legacy of militarism and masculinity, serving stories of humanity using technology to ward off futuristic invaders. After half a century of retelling the same tired stories, Neon Genesis Evangelion builds on the mecha tradition to explore the human behind its machines in the final days of a violent mythological singularity.

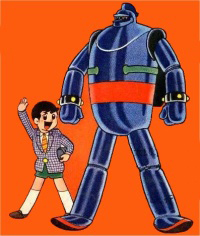

As its young audience watches similarly-aged boys and girls engage in combat on the most massive of stages, viewers escape from the fragile limits of the human body without traveling too far from it. The human characters in these augmented bodies operate their massive machine, wrecking violence on an extreme scale while also protecting their home from destruction, yet the pilots feel pain and their machines bleed. Napier points out that the "human pilot inside armored machine leads to bizarre combinations of mechanical/organic violence [...] while at the same time hinting at the organic bodies inside them with graphic glimpses of [...] blood seeping through mechanical armor" (Napier, 2001, 89). These combinations of mechanical and organic violences remind its young audience of what is natural. A fresh puddle of blood is likely enough to make one's stomach turn, but blood spattered across a dozen stories of a broken skyscraper serves up a brutal image of mortality that is unique to this fantasy genre. >When medical student Osamu Tezuka sought to create a twenty-first century Pinocchio tale, Japan's first animated television series was born (Tezuka, 1963). Created barely 5 years after the close of World War II, Astro Boy as known by his English title, appears at a time "when militarism was replaced by an ideology of peace, and when science and technology took on a new, civilian significance" (Schodt, 1988, 75). After decades of militarism and sacrifice to the war effort, Japanese children found a new hero come peacetime; the machine. After his creator abandoned him, and a brief stint as a circus performer, this boy with a nuclear reactor for a heart challenged evildoers and fought crime in the name of peace. Aside from his heart, Mighty Astro Boy possessed "a computer brain, searchlight eyes, rockets in his feet, and a machine gun in his tail" yet this "nearly perfect robot [...] strove to become more human (emotive and logical) and to be an interface between two different cultures – that of man and that of machine" (Schodt, 1988, 75). Tezuka intended his story to possess richer aspects of parody though quickly found his story stripped of all critique when "publishers wanted [him] to stress a peaceful future" (Schodt, 1988, 76). Following quickly after Astro Boy's success, the Japanese animation industry was born and an array of mecha copycats appeared. In the animation boom that followed Astro Boy's trail, entire genres were formed by Astro Boy's imitators. The first major imitator, Tetsujin 28go ("Iron Man No. 28") appears in 1958, "a technological step backward" (Schodt, 1988, 78) when compared to Astro Boy's protagonist Atom. Iron Man's main power was his strength, utilizing the standard kicks and punches along with his own rocket-powered flying to defeat evil-doers. While Atom sustained his own artificial intelligence, a teenage operator controlled Iron Man by remote control (Yokoyama, 1963). Inspired by devastation the show's creator witnessed after returning from war, along with seeing the recent American Frankenstein film, Iron Man was said to be "designed by the Japanese military as a last-ditch secret weapon to reverse its sinking fortunes" (Schodt, 1988, 78). Before the end of their popularity, the two mecha became the subject of merchandise of all sorts, remakes, and copycats still. The boxy, transforming mecha that followed, such as Gundam and Transformers, dominated the genre without many updates. The genre's first major rebirth did not come until the mid-90's, with Hideaki Anno's Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Set in the early twenty first century roughly a decade after a global catastrophe that wiped out much of Earth's population, Hideaki Anno's Shin Seki Evangelion shows a story of teenage pilots charged as the last protectors of Tokyo-3, hoping to stave off a second Apocalypse. When mysterious mythological creatures, known as Angels, appear Tokyo-3's defense force fails to damage their enemies The series begins as Shinji Ikari arrives, with orders by defense organization NERV, to pilot a massive humanoid fighting system named an EVA. When Shinji arrives at the underground defense facility he faces both his estranged father and his biological fighting machine at once. The boy's father, Gendo Ikari, calls the shots at NERV and offers the boy no choice but to fight for his life. The young man freezes when called to hastily called to battle, though gives in when given a glimpse of the already-wounded and broken backup pilot, Rei Ayanami. Always reserved yet precise, Rei appears the ultimate soldier whose duty as a neuters even her humanity. American-born and European-raised Asuka Soryu, the third child EVA pilot, appears well-adapted in any situation though, in reality, is just as damaged as her peers. Unlike Shinji and Rei, who internalize when facing their insecurities, Asuka takes aim at those around her as she constantly berates Shinji and calls Rei a 'doll' and a 'puppet.' Misato Katsuragi, Chief of Operations, and Ritsuko Akagi, Head Scientist, at NERV also support the young cyborg pilots as they grasp the last hope for humanity (Anno, 1995). Evangelion's conclusion is one of deconstruction, not only of its characters and plot but of the mecha genre in its entirety. We read that "through Shinji's self-questioning, the viewer is insistently reminded of the fundamental worthlessness of the power derived from the mechanical armor, thus undermining the whole basis of the mecha genre" (Naper, 102). Just as the mecha genre provides the viewer and idealized escape from the technological demands of modern life, Evangelion aids its viewer in deconstructing the genre they love. Evangelion's final episodes pay little attention to mecha or the fight against the Angels. Napier puts it best that "In the solipsistic world of Evangelion, mecha are finally unimportant except as a means to know the self. Even the human body is less important than the mind that creates its own reality" (Napier, 2001, 102). Instead of a simple rehash of mecha's same old tropes, Evangelion breathes new life into the genre right before it kills it. As the viewer's expectations of the show are denied so is the simple escape they seek, and another story takes over.

As the finale unfolds, viewers become aware that the men charged with orchestrating Earth's defense are also those planning its very end. When Shinji defeats the final Angel, one has little time to celebrate his victory. More attacks quickly follow, this time initiated by the NERV's own superiors, "pitting all its technology against humanity; so that by destroying it, Shinji's mind will evolve beyond individuality in its merge with his EVA." Without external enemies, humanity "will turn its violence upon itself and indeed self-destruct" (Petty, 2004, 4). Armageddon comes from an unexpected source; Ayanami Rei, whom we discover to be a model of disposable clones modeled after Gendo's wife and Shinji's mother, awakens (Anno & Tsurumaki, 1997). With NERV's enemies gone, human instrumentality begins and when Rei abandons her creator Gendo. Rei usurps control of Instrumentality from Gendo and becomes the god-hand that initiates singularity. After deserting Gendo, and his will, the goddess begins consuming the energy of the entire Earth. Jointly consuming and merging all of Earth's souls, Rei reaches out to Shinji Ikari. Upon merging, "he-she understands that pain is created by the barriers that isolate people into individuals" and realize that "[t]o be individual, then, means to accept pain and not run away from it and make an 'other' suffer" (Petty, 2004, 5). In the frantic and final moments after this realization, the last of Shinji's remaining consciousness decides to return to individuality, with all its pain. These actions spark a new genesis upon the devastated Earth, with our cyborg pilots Asuka and Shnji playing the roles of Eve and Adam. These events provide for the creation of "a new order that unites people into an intimate communal consciousness," as argued by Genevieve Petty in her Carolyn Krause Maddox Award winning essay (Petty, 2004, 5).

Upon the completion of the show and its subsequent film, Assistant Director Kazuya Tsurumaki shared his own interpretation of the show's message and finale. The interview was first printed in the Red Cross Book, a pamphlet sold to Evangelion movie-goers, but reprinted on Evangelion fansites. In the end, Evangelion is a story about communication; an argument to get out and do it. He cites a scene in Episode 3, when Shinji and Misato "are having a casual morning conversation, but are not looking at each other. Like they looking through a slightly opened door, but not connecting. [...] It's no wonder there was a lot of distant, awkward communication." When Earth's saviors could not even look each other in the eye, the show speaks to its own fans. Rather than shut themselves in all day to enjoy their respective media, anime fans could use a dose of the world around them despite the pain and confusion it brings. Kazuya goes so far as to say that "it's useless for non-anime fans to watch it. If a person who can already live and communicate normally watches it, they won't learn anything." Media consumers should abandon their cyborg tendencies, giving up the television for real world human experience. When Donna Haraway said that the "cyborg has no origin story," (Haraway, ), no Genesis. To all the natural souls, like those born and reborn in the world of Evangelion, a failed singularity offers a chance to start over again. This rebirth serves to awaken anime fans obsessed with giant robots, phallic weaponry, and militarism. Rather than engulf oneself in a medium which offers feedback but accepts none, the creators stress the need to reach out and connect humanity. BibliographyAnno, H. (Director). (1995). Neon Genesis Evangelion. Japan: Gainax, Ltd. |