The Transformation of Training and Communication in the Workplace Robert Shultz In order to maximize the efficiency and volume of their businesses, many companies have considered employing different forms of physiological analysis on their workforce. As a result, many businesses have hired epistemologists who use their knowledge of human thought processes to form curricula for worker training. The goal of these consultations is to organize training programs to maximize an employee's ability to engage with the technology associated with their jobs. Businesses have grown to view their staff as one cybernetic organism that interfaces with the technology of its occupation with varying degrees of success depending on the quality of their training.

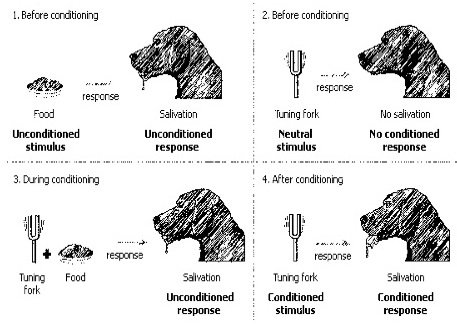

The value of a relationship between a business and its employees is dependent upon how employers choose to view their employees. While some employers see their workforce as a group of mindless automatons, other companies picture their workers as capable individuals who are able to construct dynamic solutions to complex problems. The different prisms through which staffers are seen are mainly dependent on the conditions of the workplace. A factory foreman may find it appropriate to view his or her manufacturers as mechanical minions who perform a repetitive task if they are properly taught and supervised. Many of these employers can be categorized as behaviorists. Behaviorism is a philosophy of education that views learners as empty vessels that have to be filled with knowledge (Doms and Troske Pg. 6). One of the most famous behaviorist was Ivan Pavlov, and in his well-known canine drooling experiment, he proved dogs could be trained to drool on command when he associated food with the sound of a bell. Pavlov would later be noted in work done by Burrhus Frederic Skinner on a process known as conditioning. Skinner saw learners as machines that could be taught to retain information if they were effectively conditioned.

There are multiple types of conditioning, and employers use all of them. Classical conditioning involves the association of a neutral stimulus with a specific reflex. A bell or whistle to acknowledge the beginning and end of a workday is one of the oldest examples of classical conditioning. Aversive conditioning involves a subject carrying out actions to avoid an adverse stimulus. Some examples of this in the workplace are docking pay, cutting overtime hours, or termination due to a lack of performance. A third form of conditioning is operant conditioning, in which workers are encouraged by an incentive system of bonuses and promotions to reward outstanding performance. All employers use these methods in one form of another, but not all businesses use behaviorist philosophies when dealing with employees. A foil to this doctrine is the constructivist view of learners, where the novice is thought to potentially have prior knowledge of her or his position, and responds best to an interactive learning environment where she or he helps to construct the curriculum. The first promoter of constructivism was Jean Piaget, to be followed by John Dewey and Jerome Brunner. They believed that students or workers would perform better when they feel that they have a role in deciding how educational material is presented to them (Doms and Troske Pg. 192). Constructivism was a radical point of view in 1923 when it was introduced, but now it has a foothold in many corporations' training policies. These companies have generally found success when implementing interactive techniques in training methods. On average, employers that use constructivist-training models find their employees to be more satisfied with their positions. In other words, when employees feel that they have a say in how management engages them, they usually are more content and stay with the company. Businesses like this because it reduces their turnover and overhead. While a reader may assume constructivism has credence over behaviorism, the most efficient procedure for educating a work force is usually a mixture of the two and depends on the employees and their positions. In the postmodern era of mass communication and decisions, many new jobs have been created to manage the complexities that are associated with advances in technology. Many businesses have noticed that these jobs require much more cognition than that of a factory line worker, and as a result some companies have developed a more constructivist platform to educate and communicate with their employees. Chris Hables Gray, Ph.D., describes his experiences working for Hewlett Packard as enjoyable. He notes that “before the ‘higher ups' would change the production method for a microchip, they would ask their engineers and the lower level assembly line people if it was a good idea” (February 25, 2010). As a general rule, Hewlett Packard has had a philosophy of little-to-no middle managers, and good vertical communication amongst the ranks. This type of constructivist thinking is what separates Hewlett Packard from Sun Microsystems and Microsoft, who disassociate their rank and file employees from their executives with a flurry of middle managers. In an increasingly technical world, the effective communication and education of a workforce is essential for efficient production. When companies view their staff as a larger entity or cyborg, they enable the use of psychological techniques for training technological interfaces. While it may seem as though behaviorist models work for blue collar jobs and constructivist methods work for white collar workers, the truth is that neither system is fully appropriate for educating a workforce. As businesses make the transition from mainly behaviorist styles to a mixture of teaching techniques, they generate more efficiency with lower costs. Hopefully, as more businesses expand their view of their employees, workers will be listened to by their superiors and allowed to make more decisions. As a result, employees will be loyal to their companies and increase the quality of their work -- a truly win-win situation. Work Cited:

Shoshana Zuboff (1988): In the Age of the Smart Machine.

Basic Books, Inc. page 47 part 1

Images:

Building a Robot. Bots.inc. Nov 11 2011 http://www.mnn.com/sites/default/fi

les/main_robot_2.jpg

|